(RNS) — Jimmy Carter’s improbable ascent to the White House in 1976 was abetted in no small measure by his probity and his evangelical rectitude. Indeed, it is nearly impossible to imagine Carter, the one-term governor of Georgia, winning the presidency had it not been for the culture of corruption that had surrounded the Oval Office. Lyndon Johnson had lied to Americans about Vietnam, and Richard Nixon had lied about, well, just about everything.

Carter’s pledge that he would “never knowingly lie” to the American people struck a chord, and although Carter’s term as president is generally regarded as something less than unalloyed success, no one — not even his legion of detractors — has credibly accused him of misleading the American people during his time in office. Put another way, Carter, whatever his shortcomings as president, redeemed the presidency from the culture of deceit so abundantly evident during the Nixon administration.

But one of the many paradoxes surrounding Carter’s presidency is that he was unable to fend off the deception of his fellow evangelicals, including a couple of preachers named Jerry Falwell and Billy Graham. Their duplicity may not have been responsible for Carter’s political demise, but it certainly contributed.

The roots of the religious right lie in the cancellation of the tax-exempt status of Bob Jones University, a fundamentalist school in South Carolina. On the basis of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Internal Revenue Service ruled that any institution that engaged in racial segregation or discrimination was not — by definition — a charitable institution and therefore it was not entitled to tax-exempt status.

After a district court upheld the IRS in 1970, Nixon instructed the agency to deny applications from “segregation academies,” many of them church-related schools. In the most famous case, the IRS, after years of warnings, finally revoked the tax exemption of Bob Jones University on Jan. 19, 1976, thereby provoking an outcry from politically conservative evangelical leaders. “In some states,” Falwell famously complained, “it’s easier to open a massage parlor than to open the doors of a Christian school.” (Falwell had opened the doors of his own segregation academy, Lynchburg Christian School, in 1967.)

As the religious right geared up to oppose Carter’s reelection in 1980, evangelical leaders repeatedly blasted Carter for denying tax exemptions to segregated religious schools, what they characterized as “government intrusion into private education.” But their ire was misdirected. The IRS policy was formulated during the Nixon administration, and Bob Jones University lost its tax exemption on Jan. 19, 1976, when Gerald Ford was president; Carter was inaugurated a year and a day later. That day was, in fact, an important day for Carter, but not because he was in any way responsible for rescinding Bob Jones University’s tax exemption. Carter won the Iowa precinct caucuses that day, his first major step toward capturing the Democratic presidential nomination.

Politically conservative evangelical leaders, however, intent as they were to turn Carter out of office, shrugged away the niceties of facts. They persisted in blaming Carter for the IRS action, even though Carter had nothing whatsoever to do with it.

Several evangelical preachers also engaged personally in activities that pushed the bounds of credibility. In January 1980, as Carter faced reelection, he recognized (belatedly) that his support among evangelicals, who had helped propel him to the White House four years earlier, had ebbed. In an attempt to rebuild that support, Carter addressed the National Religious Broadcasters, meeting in Washington, D.C., and then invited key evangelical leaders to the White House for breakfast the following morning, Jan. 22, 1980.

Carter thought — inaccurately, it turned out — that he could placate them with bromides about faith or religious freedom, but these leaders of the religious right were more interested in talking about social issues like abortion and gay rights.

Following the meeting, Falwell began recounting to various audiences and political rallies across the country how he had asked Carter why “practicing homosexuals” served on the White House staff. Carter, according to Falwell, replied, “I am president of all the American people and I believe I should represent everyone.” Falwell’s rejoinder: “Why don’t you have some murderers and bank robbers and so forth to represent?”

As a tape recording of the White House gathering demonstrated, however, the president made no such comment. Falwell, in fact, had fabricated the entire exchange in an apparent attempt to discredit Carter in the eyes of evangelicals.

If Falwell was guilty of deceit to advance his political ends, Billy Graham, the most famous and most respected evangelical of the 20th century, was disingenuous, if not duplicitous. On Sept. 12, 1980, less than two months before the election, Graham called Paul Laxalt, chair of Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign, and offered to help any way he could short of a political endorsement. Eleven days later Graham sent a letter to Robert Maddox, Carter’s religious liaison, insisting that he, Graham, was “staying out of” the campaign.

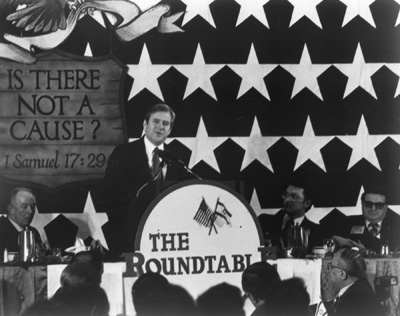

Even earlier, Graham and Bill Bright, head of Campus Crusade for Christ, had convened a gathering of evangelical preachers in Dallas for “a special time of prayer” to discuss how to dislodge Carter from the White House. Just weeks prior to that gathering, Maddox had visited Graham at his home in Montreat, North Carolina, and reported that Graham “supports the President wholeheartedly.”

Graham’s actions were eerily reminiscent of his comportment 20 years earlier during the presidential campaign between Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy. On Aug. 10, 1960, Graham sent a letter to Kennedy, the Democratic nominee and a Roman Catholic, pledging that he would not raise the “religious issue” during the campaign. Eight days later Graham convened a gathering of Protestant ministers in Montreux, Switzerland, to discuss how they could deny Kennedy’s election in November.

Later in the same campaign Graham visited Henry Luce at the Time & Life Building and, according to Graham’s autobiography, said, “I want to help Nixon without blatantly endorsing him.” Graham drafted an article praising Nixon that stopped just short of a full endorsement. Luce was prepared to run it in Life magazine but pulled it at the last minute.

Graham’s desire to thwart the candidacy of a Roman Catholic in 1960 may be understandable, especially at a time (before Vatican II) of heightened suspicions between Protestants and Catholics. But on the face of it Graham’s opposition to Carter, a fellow Southern Baptist and evangelical Christian, is mystifying. One can only assume that for Graham, as well as for Falwell and other leaders of the religious right, politics trumped piety. Both preachers were willing to engage in deception in order to advance their political goals.

Jimmy Carter may have reversed the culture of deceit that had infected the presidency during the administrations of Johnson and Nixon, but he was unable to stanch the duplicity of his fellow evangelicals. Carter’s pledge to “never knowingly lie” set a standard for the presidency, but it was a standard that some of his evangelical political adversaries failed to match.

(Randall Balmer, an Episcopal priest and John Phillips Professor in Religion at Dartmouth College, is the author of “Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)