SAN ANTONIO (RNS) — “Back then, when it was going to rain, we knew we were going to lose somebody,” said Linda Davila about her San Antonio, Texas, neighbors a half-century ago. At the time, the South Texas city’s all-white City Council had neglected the streets and sewers in its Hispanic neighborhoods, while their residents’ voting power was diluted through at-large elections.

By the early 1970s, deaths from flooding energized the city’s Latino population to begin organizing, largely through their Catholic parishes. Communities Organized for Public Service, founded in 1974, soon turned out 500 people to attend a City Council meeting. “We were able to get a $40 million bond passed for our area to take care of the flooding,” recalled Davila, then involved as a youth group member at St. Stephen Catholic Church.

Known today as COPS/Metro, after merging with other community-organizing groups formed in the 1980s, the organization has the attention of civic leaders. No longer concerned with flooding alone, it has advocated against spending public funds on stadium projects and for putting money instead into public amenities such as parks, libraries, a new community college, a low-cost diabetes center, workforce training and education funding.

COPS/Metro is “the nagging conscience in the back of the minds of the City Council and mayor,” as the organization fights “for public services and for infrastructure for the working poor and for the working class,” said Jon Taylor, professor of political science at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

San Antonio voters also now elect representatives by district, taking the city back from a handful of “big-money elites,” in the words of Sonia Rodriguez, a San Antonio resident and former COPS president.

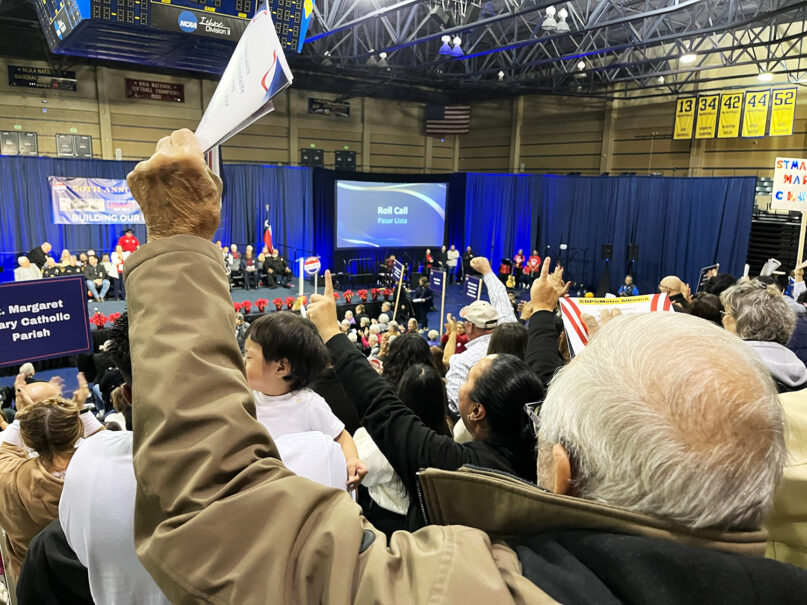

In December, more than 1,000 people packed an athletic arena at St. Mary’s University to launch a yearlong celebration of the organization’s 50-year history — and to plan for its future. Sitting with their churches amid the electric energy of a political rally, the crowd cheered as their pastors and lay leaders secured commitments from the city’s political and business leaders to work together on a variety of initiatives.

They are also the leading example of a movement that has revitalized a strategy of community organizing that originally spread throughout the U.S. at the tail end of the Great Depression. Saul Alinsky, a community activist and political theorist who wrote “Rules for Radicals,” and others founded the Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago in 1940, rallying with leaders, including clergy, in impoverished, often urban, neighborhoods to improve residents’ lives.

Led by Ernesto Cortés Jr., COPS revised Alinsky’s tactics to push more deeply into congregations, especially Catholic parishes, developing the organizing skills of their lay members, particularly women, and turning them into community leaders.

“What changed in San Antonio was a real further grounding of organizing in parishes, in the life of ordinary Catholics, in the Catholic social tradition,” said Nicholas Hayes-Mota, assistant professor of social and theological ethics at Santa Clara University in California. “It’s in San Antonio with COPS that you see a real deepening of community organizing’s relationship to the Catholic Church.”

Cortés grew up on San Antonio’s impoverished west side and returned to the city to agitate and organize those same disempowered, often Mexican-American communities after studying with Ed Chambers at the Industrial Areas Foundation Training Institute in Chicago.

His “genius” was seeing “the potential in people that others overlooked, even that they couldn’t see in themselves” and “working patiently with them,” said Joe Rubio, who took over Cortés’ position as West/Southwest Industrial Areas Foundation co-director in 2021 after Cortés stepped back to become senior adviser.

Recognizing the importance of his family and Catholic faith in his own life, Cortés made faith and family a core part of how COPS became successful, even as he shied away from the spotlight. Believing fame was detrimental to organizing, he attempted to keep a low profile, even after he was awarded a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1984.

Today, Hayes-Mota said, COPS/Metro is “one of the most historically influential and important” faith-based organizing groups in the U.S.

While its dues-paying member institutions are still primarily Catholic churches, as it turns 50, COPS/Metro includes Baptist, Episcopal, Unitarian Universalist, Church of God in Christ, Presbyterian and United Methodist Church congregations, all of which took part in the anniversary celebrations, as did a few secular community institutions.

“We’re really proud to be in community with the other churches in town,” said Mike Phillips, a COPS/Metro leader at First Unitarian Universalist Church, which is on the northern, wealthier side of San Antonio.

RELATED: On US-Mexico border, Catholic leaders prepare for return of Trump anti-migrant regime

COPS/Metro is the founding member of the West/Southwest Industrial Areas Foundation, a regional affiliate for the IAF, where Cortés’ model of empowering lay members of congregations has spread to its chapters from California to Nebraska to Louisiana.

Elizabeth Valdez, director of the IAF in Texas, said, “The issues come from the bottom up.” The organizations hold house meetings, or listening sessions, “ where we hear what is the cry of the people, what are the major issues that they are concerned about,” she said.

Most importantly, they “ identify the leaders that want to work in the communities and want to work with others to change, to transform those issues.”

COPS/Metro has also influenced Faith in Action and The Direct Action and Research Training Center, or DART, according to Hayes-Mota. “We all were inspired in training by Ernie Cortés,” said Ana Garcia-Ashley, the executive director of Gamaliel, a prominent faith-based organizing network with 41 affiliates in 13 states. Garcia-Ashley, who was trained by COPS leaders in the 1980s, calls Cortés “a genius of organizing.”

Among some Catholics, these groups, like COPS/Metro, are controversial because of their connections to Alinsky’s methods.

San Antonio’s archbishops have historically supported COPS, and through the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has funded the work of COPS/Metro and similar organizations.

But in the last 20 years, conservatives in the church have begun to warn against Catholic participation in Alinsky-related groups. These concerns were only heightened when it became known that former President Barack Obama had gotten his start in community organizing with Gamaliel, said Hayes-Mota.

In 2020, EWTN, the popular Catholic television network, released a documentary on Alinsky titled “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” accusing the man who founded the Industrial Areas Foundation of being a Marxist and a socialist.

Alinsky, an agnostic Jew who partnered closely with Catholics, frequently spoke against communism in his lifetime, and some of today’s socialist thought leaders have argued against his methods, saying they “(dismiss) radical politics.” Even so, Hayes-Mota said the EWTN documentary “has circulated widely, to the point that many priests, I’ve heard from organizers and some bishops, will actually cite it when they learn about an IAF initiative.”

RELATED: Report: ‘Catholic McCarthyism’ threatens bishops’ anti-poverty push

Pope Francis, for his part, has met with leaders and organizers of the West/Southwest Industrial Areas Foundation in 2022, 2023 and 2024, once calling their work “atomic,” according to organizers.

In San Antonio, many Catholics have a profound allegiance to COPS/Metro. Sister Pearl Ceasar, a member of the Congregation of Divine Providence, said she became a sister after being horrified by the segregation she saw growing up in Louisiana. “The church has a major role in bringing about change in our society,” she said.

After moving to San Antonio, she began working with COPS and has served as an organizer with them for 40 years. Before, the parishioners at St. Alphonsus, located in one of the poorest neighborhoods of San Antonio, would avoid the public housing projects, Ceasar said, “ because they were afraid of the people who live there,” but that all changed within a few years after COPS was founded.

She remembers a proud moment when a parish leader called her to say that, after walking the neighborhood to get out the vote and invite people to the parish, “we became church.”

“ What the organizing process does in teaching Scripture is teach who the community is,” Ceasar said.