What brand of Christianity is offered at Hillsong Church?

Basically, it’s a slightly tamed version of evangelical Christianity, blended with Gen X pop-rock music, delivered by talented preachers with tattoos and ripped jeans. And then there are the celebrities who show up from time to time — which really helps create viral social-media stuff.

That’s the formula readers encounter in a must-read New York Times feature that ran the other day, when what was already an important story about evangelicals in the Big Apple gained the kind of editorial punch provided by sex, scandal and ties to Justin Bieber. Here’s the double-decker headline on this latest story by religion-beat pro Ruth Graham:

The Rise and Fall of Carl Lentz, the Celebrity Pastor of Hillsong Church

A charismatic pastor helped build a megachurch favored by star athletes and entertainers — until some temptations became too much to resist.

All of the glamour and celebrity details are important and valid. However, there is another angle of this story that is totally missing. The words “Assemblies of God” do not appear anywhere in this lengthy Times feature.

Truth is, Hillsong grew out of the Assemblies of God, an important Pentecostal and charismatic Christian flock with about 70 million members around the world. And why did Hillsong cut its ties to the Assemblies, other than a yearning for independence from denominational authorities and perhaps to erase a some bad memories?

Hold that thought, because we will come back to it. Here is a crucial chunk of summary material containing the important themes that provide the structure for this Times piece:

Even in the contemporary era of megachurches, Hillsong stands apart. Founded in Australia under a different name in the 1980s, its great innovation was to offer urban Christians a religious environment that did not clash with the rest of their lives.

At a time when many Americans have abandoned regular churchgoing, Hillsong attracts thousands of young churchgoers through soaring music and upbeat preaching. If anything, it is cooler than everyday life, with celebrities like the actor and singer Selena Gomez and the N.B.A. star Kevin Durant showing up at Sunday services.

By now, Hillsong is not just a church, but a brand. Hillsong is a look: neutrals, streetwear, body-conscious fashion. And it is a sound, too. The church’s bands have won a Grammy. Their most popular song, the soaring ballad “Oceans (Where Feet May Fail),” has been streamed more than 235 million times on Spotify. And the formula works. The global church now has congregations on six continents, and claims an average attendance of 150,000 people weekly.

The heart of this story is the life and times of Carl Lentz, who for some reason is never called the Rev. Carl Lentz (more and more journalists seem to be skipping over Associated Press style guidelines for clergy titles).

It’s clear that Lentz is a charismatic leader and preacher who helped the Hillsong fire fall in New York City. Readers learn quite a bit about his looks and sense of cool, as in this quick summary: “Women’s Wear Daily described Mr. Lentz’s ‘uniform’ as a Saint Laurent leather jacket, ripped jeans and a low-cut T-shirt. He often sported a Rolex, too.”

It is interesting that the story offers zero insights into this dynamic preacher’s sermons — which would seem, to me, to be a crucial part of this drama (and they’re easy to find online, too). For example, what did he say in his final two-part sermon series — “I’m Not Slowing Down” — which was delivered as scandal clouds were building overhead.

When writing about preachers, it’s important to pay attention to the skills that led to their success. What did this man say that pulled in the crowds?

I know, I know, details about Justin Bieber are way more important with editors, along with quick nods to contacts with the likes of Oprah and various Kardashians.

Thus, here are the details that the Times offered right up top:

In the summer of 2017, the singer Justin Bieber abruptly canceled the remainder of a concert tour that had taken him across six continents in 16 months. Mr. Bieber cited fatigue; his fans fretted. But on the tabloid website TMZ, a more hopeful narrative quickly emerged. The 23-year-old singer left the tour because he “rededicated his life to Christ” thanks to a pastor named Carl Lentz, leader of the New York City branch of the global megachurch Hillsong. The pastor and the pop star were inseparable, the gossip site reported. Two days later, the site reported that Mr. Bieber saw Mr. Lentz “as a 2nd father.”

That year Hillsong and Mr. Lentz became a fixture on TMZ, always in flattering items citing unnamed sources. One article reported that at Hillsong, “Justin worships in total peace, and at least feels he’s treated like a regular person.”

Sort of.

The Times piece does a great job of describing the hipper-than-thou realities of life in the quartet of “Hillsong East Coast” congregations (weekly attendance of 7,000) led by Lentz, including efforts to put ordinary off-the-street volunteers humble while putting spotlights on the rich and famous. As someone who has covered quite a few rock shows and pre-release movie events, I was struck by these details.

On Sundays, a team of congregants working as volunteers prevented anyone without the right badge from wandering backstage, and only a few had clearance to enter the green room stocked with a lavish catering spread and changes of clothes to fit Mr. Lentz’s increasingly particular tastes.

As part of the information about the fall of Lentz, readers learn that the global Hillsong operation was actually founded by the Rev. Brian Houston of Australia — who created his own model for church life built on principles seen in thousands of other megachurches..

Anyone who has followed evangelical life in recent decades can spot the spiritual DNA here:

Hillsong’s model is what is known as “seeker sensitive,” a consumer-oriented approach that aims to attract people wary of or unfamiliar with traditional church. Instead of old hymns and dry sermons on Sunday morning, Hillsong and the churches like it offer a slick concert punctuated by a “message” that often sounds more like a self-help seminar. Mr. Houston’s rules for leaders in Australia instruct that a Hillsong sermon “leaves people feeling better about themselves than they came.”

How did Lentz get connected to this flock?

… In the early 2000s he made his way to Australia, where he attended a school operated by Hillsong Church. Mr. Lentz interned for Mr. Houston, who founded the church with his wife, Bobbie, and befriended his oldest son, Joel. By 2010, Hillsong was opening its first church in the United States, and Mr. Lentz and his wife, Laura, moved from Virginia to New York to help Joel Houston lead it.

This is where it really would have helped to offered more information about the Assemblies of God roots of the Hillsong mini-denomination.

The Times piece briefly mentions, while discussing the sins of Lentz:

Mr. Houston has been forced to confront scandal before. An Australian commission found in 2015 that he had failed to inform the police about child sexual abuse accusations against his own father, another prominent pastor in Australia. Mr. Houston’s father was accused in the late 1990s of sexually abusing a young boy decades earlier. Mr. Houston pressed his father, who has since died, into retirement when he found out.

Three years after those 2015 headlines in Australia, Hillsong pulled out of the Assemblies of God. Click here to read a Christianity Today story about that news in 2018.

Then there is this piece at The Guardian about the “sins of the father” connections between Houston, Hillsong and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison. It notes that Brian Houston had actually served as the leader of the Assemblies of God in that nation.

A child sexual abuse victim of Hillsong founder Brian Houston’s father Frank has questioned the “audacity” of Scott Morrison continuing to support Houston, and the possibility Houston may have been invited to accompany the prime minister to the White House in September.

Frank Houston, who died in 2004, headed the Assemblies of God church in New Zealand until the early 70s, while Brian was the head of the Australian branch from 1997 until 2009, and founded Hillsong in 1983.

Frank was accused of sexually abusing nine boys, and in 2015 the royal commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse found Brian had failed to report his father’s abuse to police.

So what’s my point here?

Let me state once again that the Times piece does a fine job when it comes to describing the celebrity culture surrounding Lentz and the role that may have played in his recent fall from grace.

However, I would argue that the history of Hillsong is also crucial, in that it offers yet another example of what happens when powerful church leaders cut their denominational ties and set up their own shops, complete with an education system, parachurch networks and handpicked clergy who thrive because of their ties to the Alpha Male at the top.

Trust me, I know that it is hard to cover these totally independent movements that tend to operate behind closed doors — without denominational structures that at least try to provide systems of accountability. I also know (#duh) that men like Theodore McCarrick have been able to thrive in ancient ecclesiastical systems. “Uncle Ted” was a kind of celebrity inside the Vatican, as well as with journalists in New York City and Washington, D.C.

In this case, I think it would have been helpful to have provided more than a few sentences about the roots of Hillsong, including its flight from the huge, growing, Assemblies of God movement. That split was amicable, according to public statements. However, I would say that the flaws seen in Australia may have been clues pointing to larger problems in Brian Houston’s independent operation.

If you want to read an interesting meditation on the weaknesses found in that kind of culture, see this David French essay at The Dispatch entitled “The Crisis of Christian Celebrity — ‘The heart is deceitful above all things.’ “ The thread on this tweet is also worth exploring.

I’m getting a lot of good and thoughtful responses to my Sunday essay. I could have written 2,000 more words on the role of staff and boards in enabling abuse, but in lieu of that, here are a few tweets. /1 https://t.co/BDNywgc3e9

— David French (@DavidAFrench) December 6, 2020

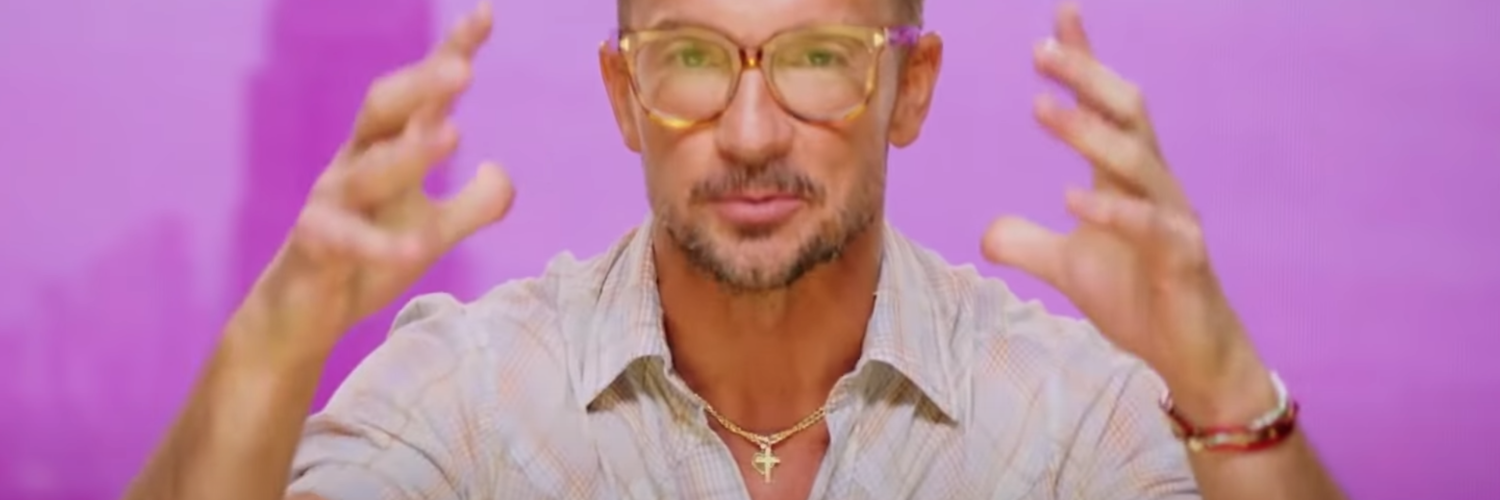

FIRST IMAGE: Screen shot from Hillsong YouTube of the sermon, “I’m Not Slowing Down.”