“[Jesus] said, ‘To what shall we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable can we use for it? It is like a mustard seed that, when it is sown in the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on the earth. But once it is sown, it springs up and becomes the largest of plants and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the sky can dwell in its shade.’”

—Mark 4:30-32

A chief paradox in our Christian faith is the cyclic nature of consolation and desolation. Many who ascribe to the sunny spirituality theology (e.g., prosperity gospel) remain puzzled as to how—and why—a faithful Christian would experience an increase in the intensity and/or frequency of heavy crosses.

I confess that, even as a cradle Catholic who was brought up to “offer it up,” I held only a vague and weak notion of what it meant to suffer. Likely, I still do, but my hope is that, as I grow in my faith, I gain greater perseverance—a key to suffering well—when unexpected heavy crosses happen upon my life.

Because God is always good, even when our lives take a spin downward, we are assured that every period of desolation will end. And we will emerge into a field of consolations. The opposite is true, however: every season of consolation is meant to prepare us for the next cross.

In this parable, we learn a hard but beautiful truth: growth gives way to drought, and drought gives way to growth.

And another: great outcomes can result from small and humble beginnings.

As we look to nature, we glean a proper understanding of the cyclic rhythms that punctuate life. Scarcity cycles back to abundance; long droughts to cleansing rains; death to life, and life to death. Nothing is lost when we consider the parable of growth and drought, because we learn that everything carries within it the potential for life and for death.

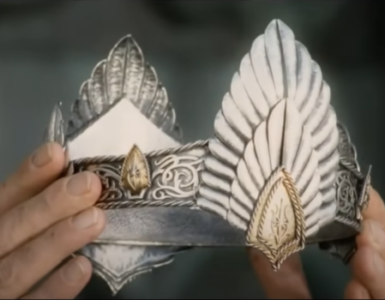

More than that, every death can result in eternal life somehow. When I married into my husband’s family, I learned that the MacEwan clan of Scotland had a family crest with the motto “Reviresco,” which translates loosely into “I grow strong again.” The image is of a flattened tree stump with a tiny sapling sprouting in the middle of it.

Death creates space for new life to emerge within us, too. Every loss, every suffering, every cross is meant as an invitation for us to become more than what we were before the loss or suffering or cross. We are not meant to remain idle or stagnate in our existence. Instead, God’s wisdom is that suffering, while not part of His perfect will, can be resourceful. It can be used for a greater good that bears upon it the longevity of a legacy.

The parable of the mustard seed also tells us that what begins as a meager offering, when given to God, will blossom into something beyond our wildest fathoming. I think about every type of tree and flower and vine and bush. My husband prunes the landscaping in the fall, and every year, without fail, I wince when I see how paltry they’ve become—some barely visible above ground. And every summer, without fail, I am amazed (as if witnessing this for the first time) that they have burgeoned into lush, vibrant greenery, giving forth berries and flowers and all sorts of foliage.

It’s incredible the hope we can find all around us when we pay attention. I find nature to be a grand teacher of spiritual lessons, because it’s the image that speaks to us without a spoken word. So much can be harvested from such meditations. The little mustard seed, barely visible to the human eye, carries the potential for greatness.

We, too, though insignificant in the grand scheme of life, hold that same potential inside of us. Perhaps that is a small consolation when we, like the bushes and vines when freshly pruned, feel the sting of suffering. In our weakness and littleness, it is tempting to forget who we are and what we are meant to become. Yet, the smaller we allow ourselves to be in God’s hand, the more fruit we will bear for the good of the world and for God’s glory.

✠