I just did a Google Images search for the words “American Evangelicals” and it yielded — on the first screen — as many images of Vladimir Putin as of the Rev. Billy Graham. If you do the same thing on Yahoo! your images search will include several pictures of George Soros.

I don’t need to mention the number of images of Donald Trump, a lifelong member of the oldline Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Do I?

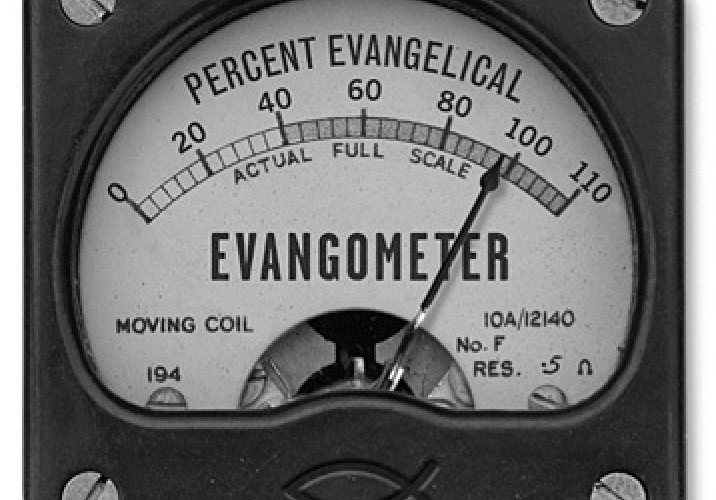

The obvious question — one asked early and often at GetReligion — is this: “What does the word ‘evangelical’ mean?” But that really isn’t the question that needs to be asked, in this context. The more relevant question is this: “What does ‘evangelical’ mean to journalists in the newsrooms that really matter?”

I raise this question because of a remarkable passage in the New York Times feature about the tragic, early death of Rachel Held Evans, a highly influential online scribe whose journey from the conservative side of evangelicalism to liberal Protestantism has helped shape the emerging evangelical left. The headline: “Rachel Held Evans, Voice of the Wandering Evangelical, Dies at 37.”

Before we look at that news story (not a commentary piece) let’s pause to ask if the word “evangelical” has content, in terms of Christian history (as opposed to modern politics).

For background see this GetReligion post: “Yes, ‘evangelical’ is a religious term (#REALLY). You can look that up in history books.” That points readers toward the work of historian Thomas S. Kidd of Baylor University, author of the upcoming book, “Who Is an Evangelical?: The History of a Movement in Crisis.” Here is a crucial passage from Kidd, in a Vox explainer piece:

The most common definition of evangelicalism, one crafted by British historian David Bebbington, boils down to four key points. First is conversion, or the need to be born again. The second is Biblicism, or the need to base one’s faith fundamentally on the Bible. The third is the theological priority of the cross, where Jesus died and won forgiveness for sinners. The final attribute of evangelicals is activism, or acting on the mandates of one’s faith, through supporting your church, sharing the gospel, and engaging in charitable endeavors.

In today’s media, “evangelical” has shifted from the historic definition to become more of a rough political and ethnic signifier.

The news media image of modern evangelicalism, he added, “fails to recognize most of what was happening in the weekly routines of actual evangelical Christians and their churches. As Bebbington’s definition suggests, most of a typical evangelical’s life has nothing to do with politics.”

Now, from my perspective, the most important thing that needs to be said about the work of Rachel Held Evans is that she openly challenged the DOCTRINAL roots of evangelical Christianity, as opposed to focusing merely on politics. While she noted that she voted for Hillary Clinton and opposed Trump, that was not the main thing on her mind and heart when she went online. Yes, there were political implications to her doctrinal views — but doctrine was the key.

With that in mind, let’s work our way through a remarkable chunk of that Times piece, starting with:

An Episcopalian, Ms. Evans left the evangelical church in 2014, she said, because she was done trying to end the church’s culture wars and wanted to focus instead on building a new community among the church’s “refugees”: women who wanted to become ministers, gay Christians and “those who refuse to choose between their intellectual integrity and their faith.”

My question: What is “the evangelical church”? Singular and united?

There is no such thing. Evans may have left evangelicalism. But there is no one evangelical “church” or denomination. Instead, evangelicalism has always been defined as a movement in a variety of denominational settings — including the “evangelical” wing of Anglicanism and, thus, the Episcopal Church. There are even arguments about whether one can be an “evangelical” Catholic (as a former evangelical, I vote “no” on that one).

Moving on. Read carefully and note the lack of attribution in these fact paragraphs. This is coming straight from the heart.

Ms. Evans’s spiritual journey and unique writing voice fostered a community of believers who yearned to seek God and challenge conservative Christian groups that they felt were often exclusionary.

Her congregation was online, and her Twitter feed became her church, a gathering place for thousands to question, find safety in their doubts and learn to believe in new ways.

Her work became the hub for a diaspora. She brought together once-disparate progressive, post-evangelical groups, and hosted conferences to try to include nonwhite and sexual minorities, many of whom felt ostracized by the churches of their youth.

She wrote four popular books, which wrestled with evangelicalism, the patriarchy of her conservative Christian upbringing, and documented her transition to a mainline Christian identity, which moved away from Biblical literalism and to affirmation of L.G.B.T. people.

Once again, note the emphasis on changes in doctrine.

I think that it’s wrong to define conservative evangelicals in terms of political decisions. Thus, I think that it’s wrong to define liberal evangelicals, or former evangelicals, in political terms. Once again: Evans changed her mind on doctrines and then those choices had political implications. The same thing happens with doctrinal convictions on the conservative side of the doctrinal aisle, as well.

Frequent GetReligion readers may recall that I once had a chance to ask Graham to define the term “evangelical.”

The world’s best-known evangelist responded, “Actually, that’s a question I’d like to ask somebody, too. … You go all the way from the extreme fundamentalists to the extreme liberals and, somewhere in between, there are the evangelicals.” Ultimately, Graham said an “evangelical” is someone who preaches salvation through faith in Jesus and believes all the doctrines in the Nicene Creed — especially in the resurrection.

I brought that up, several years ago, in a discussion with the Rev. Rick Warren, one of evangelicalism’s defining voices in recent decades.

Warren affirmed Graham’s stress on doctrine, of course. Then he opened up about his own experiences with journalists. The following is long, but essential:

During the administration of President George W. Bush, he said, most journalists “seemed to think seemed to think that ‘evangelical’ meant that you backed the Iraq war, for some reason or another. … Right now, I don’t think there is any question that way too many people have decided that evangelicals are people who oppose gay rights — period. That’s all the word means.”

Warren based this judgment on his experiences during 22 interviews with major newspapers, magazines and television networks — a pre-Christmas blitz marking the release of an expanded, 10th anniversary edition of his book “The Purpose Driven Life: What On Earth Am I Here For?” …

By the end of that media storm, Warren said members of his team were starting to cast bets on whether the perfunctory gay-marriage question would be the first, or the second, question in each interview. On CNN, interviewer Piers Morgan noted that the U.S. Constitution and the Bible are “well-intentioned” but “inherently flawed.” Morgan continued: “My point to you about gay rights for example — it’s time for an amendment to the Bible.” …

Time after time, said Warren, interviewers assumed that his beliefs on moral and cultural issues — from salvation to sexual ethics — were based on mere political convictions, rather than on the Bible and centuries of doctrine.

“I’ve decided that don’t have faith, so politics is their religion,” he said. “Politics is the only thing that is really real to many people in our world today. … So if politics isn’t at the center of your life, then many people just can’t understand what you’re saying.”

So where does that leave us with Evans and the media coverage of her tragic death?

The bottom line: Focus on the doctrines. In terms of the doctrines that she affirmed, and denied, Evans was a leader among those who left mainstream evangelicalism and moved to the doctrinal left, especially on issues of sexual morality. But were there other crucial doctrinal issues, as well?

With that in mind, I would like to ask those who knew her work inside-out where (based on her writings) she stood on the doctrinal questions — yes, the “tmatt trio” — that I always ask when probing fault lines inside modern Christianity. URLs would be helpful for reporters, I would think.

(1) Are biblical accounts of the resurrection of Jesus accurate? Did this event really happen?

(2) Is salvation found through Jesus Christ, alone? Was Jesus being literal when he said, “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (John 14:6)?

(3) Is sex outside of marriage a sin?