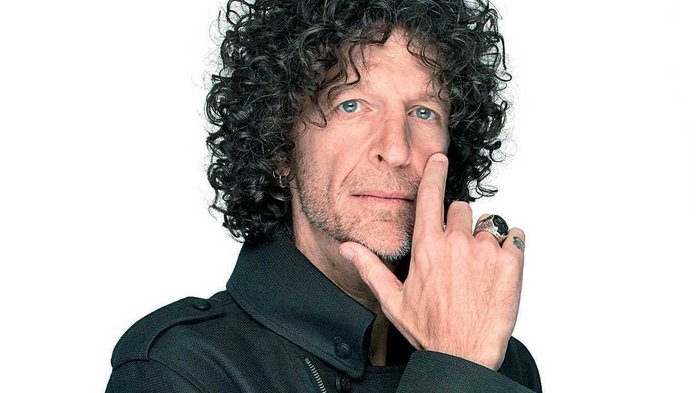

Howard Stern gave a remarkable two-part interview last week on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross. In terms of cultural encounters, that’s interesting in and of itself.

A good many social conservatives — OK, I’ll own this — have usually found it easier to think of Stern as one of the harbingers of the apocalypse. If he was not one of the four horsemen, he was the nearly naked drunken guy dancing with abandon somewhere in the end times parade, much to the delight of those citizens who think of Mardi Gras on Bourbon Street as the cultural high point of the year.

Writing in “Prophet of All Media” for Tablet, Liel Leibovitz makes an argument that, like Stern, is provocative. Leibovitz repeatedly compares Stern to Judaism’s prophets, and he begins with an earthy tale straight out of the Talmud about a prostitute who breaks wind and delivers a related prophetic word to her client, a rabbi.

“And it’s just the sort of story that makes the seminal text of Jewish life — often introduced to young yeshiva students as an account of God’s own mind — so transcendent,” he writes. “To imbue humans with wisdom, the ancient rabbis who compiled the Talmud realized, you need more than just a commandment; if you want humans to listen and learn, you have to embrace all the appetites and the oddities that make them human. Try to talk to us about the labors of redemption, and we might scoff at such haughty moralizing or slink away from the effort it demands. Deliver it in a good yarn about a farting prostitute, and we’re bound to laugh, think, and empathize.”

Much of Leibovitz’s argument continues in this vein, leaving the impression that apart from the occasionally unkind or crude remark, Stern surely joins the farting prostitute in having a heart of gold.

In time, however, Leibovitz reaches the mother lode of his case, with a comparison for all Americans who have set NPR as the first station on the audio devices built into their automobile dashboards. Leibovitz goes so far as to compare Stern to Terry Gross — not by mentioning their most recent interview, but by comparing the cultural effects of their respective style of interviews.

This is very long, but essential. Media professionals, let us attend:

Falling somewhere between selfies and Styrofoam packaging on the list of modern contrivances that are mildly useful yet indicative of a deeper moral rot, the celebrity interview, before Stern’s arrival, fell into one of two categories. Famous men and women who merely wanted to promote their new work could pop by a late night talk show, fake charm for a few minutes, and leave without having delivered anything too revealing. If, however, the same luminaries were in the mood for gravitas, they could go on a small number of highbrow shows, and open up under the protective canopy of Prestige Journalism. Because he realized how central celebrities had become to our culture, Stern understood that if he wanted to model to the rest of America what a normal human conversation looked like — a once basic skill eroded by years of texting, tweeting, and staring at screens — he’d have to do it by talking to the famous people they adored.

To fully understand his genius, consider the following two examples. The first is an interview with Stephen Colbert, conducted by Terry Gross in 2018. Praised to the heavens for being the greatest interviewer of this or any other time, Gross famously sits alone in her booth in Philadelphia, preferring not to be in the same room as her guests. Then, she asks informed questions in the calm tone only a Very Smart Person may command, a soft-spoken priestess of authority and knowledge. Here’s how she began her interview with the late night host:

When you started doing The Late Show as opposed to The Colbert Report and you were able to drop the Colbert Report persona, did you know what your authentic voice was going to be, you know, what your voice is — like, the actual Stephen Colbert was going to be — ’cause you still have to have, like, a bit of a persona as an entertainer onstage.

It’s an intelligent question and Colbert gives an intelligent answer, saying things like “I would say that what I didn’t anticipate was how much I would over-correct for not doing the character.” Things took a different turn when Colbert came to Stern’s studio in 2015. Unlike Gross, Stern insists all his guests sit across from him on the couch, so that he may look them in the eye and speak to them like two normal people would. When Colbert walked in, Stern could barely hide his excitement. “There he is,” he said, “the famous Stephen Colbert. How great is this? Sit down. I can’t wait to talk to you.”

One simple act of genuine emotion begat another, and Colbert asked Stern if he was allowed to shake his hand.

Stern: You have to put on the Purell. You’re not afraid of shaking hands? You don’t worry about germs or any of that stuff?

Believe it or not, readers/listeners should prepare for religious material:

Colbert: No. I’m one of 11 children. The youngest of 11. It was filth all the time.

This, naturally, led Stern to ask Colbert about his Catholic upbringing, which led to both men opening up about their mothers, which led to a conversation about Chris Farley and Colbert’s early days as a comedian. Eventually, they got to The Colbert Report, too, but by the time they did, you didn’t feel like you were listening to a trained and licensed journalist exchanging facts and opinions with a trained and licensed guest; you felt as if you were in the room eavesdropping on two smart guys having a candid conversation. There is, of course, more than one style of effective interviewing; talking to people isn’t a zero-sum game. But there’s also a discernible difference to a Terry Gross conversation, say, and one by Howard Stern: The former often leaves you informed and unmoved; the latter frequently reminds you that whatever it is that’s going on in the country right now, we’re all in it together, so we better drop our preconceived notions and our self-obsession and listen for a while. That’s why every fifth caller or so to the Stern show eventually says something like “thanks for having so-and-so on the show; I used to really hate him but you made me see him in a whole new light.”

His summary of the Terry Gross effect is worth repeating: it “often leaves you informed and unmoved.”

Leibovitz does not make such a solid case that I feel driven to become a SiriusXM subscriber for the sheer revelatory breakthroughs of Howard Stern’s interviews with celebrities. But, like Stern’s interview with Gross, it gives me hope that even a man who seemed to embody the crassest of American culture is more complicated than I had assumed.

I want to give Leibovitz a well-earned last word:

The real shock of Howard Stern’s metamorphosis, then, isn’t watching a jagged youth mellow into a fully rounded adult, or a playful narcissist mature and realize that others exist. It’s watching the visionary who chided us for being unhealthily repressed about our bodies turn around to tell us that we’re now being careless with our souls.