By Irving Hexham

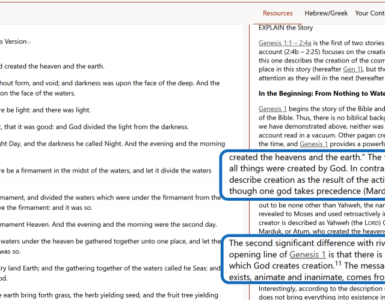

The Bible begins by proclaiming the great truth that God created the heavens and the earth. It continues by telling the story of the creation of humankind and states very clearly that all people are made in the image of God. Not surprisingly, given the fact that God is the creator of all things, we are told in Genesis 1 that he surveyed his creation and saw that it was good.

Today many people laugh at the biblical story and see it as a relic from a pre-scientific age. “Don’t Christians realize,” they say, “that we now know life was created by a process of evolution. Bible stories are fables without any relevance to the modern world.” Although this is a popular view, it is wrong. It overlooks the uniqueness of the biblical account of creation and what it really teaches about the world and our place in it.

What most secular people, and even some Christians, do not realize is just how revolutionary the story of Genesis is. To begin with, it tells us that the world God created was and is good. This may not seem very profound, but it is. It contradicts many views in popular philosophies and religions. For example, ancient traditions found in Greek and Roman philosophy saw the world as essentially bad. Buddhism and the Hindu tradition both see the world as an illusion that we need to escape. In one way or another, these and other religions teach that the earth and the material things we see around us are essentially bad and something humans need to overcome and escape from.

Plato (428–347 BC) understood the true essence of the human being in terms of an immortal soul trapped in a material body. This the Bible clearly denies. The Bible is world affirming and teaches that material things are good, not bad, and are there to be enjoyed by humans.

The Bible teaches that God created the human race—which means everyone you know and have ever met—in his own image. Thus, all human beings share the ability to establish a relationship with God and with each other. The Bible teaches us that however different people look, or seem, they share a common humanity. Once again, this teaching stands in sharp contrast with many views that are popular today.

What makes people who they are at the most fundamental level is not their ancestors or a specific culture, but the fact that they are created by God and share his image. Of course, we must not be naive and think that our background, parents, culture, and ancestry have no impact on us. Each of our personal histories is important and shapes our outlook and our lives. But whatever our histories, they can never diminish God’s image in us and in everyone we meet.

A corollary of the belief that God created humans in his image is rejection of the idea that the human races evolved from different ancestors and are therefore essentially different. Christians stood firmly against what in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was known as “scientific racism” and should continue that stand today. In the biblical perspective, there are no human races; there is only one human race that developed from common ancestors. The story of Adam and Eve, quaint as it may sound to modern ears, commits Christians to reject racism and everything derived from it.

What does all of this have to do with world religions and the increasingly religiously plural society most of us live in today? The first chapters of Genesis not only lay the foundation for all that follows in the Bible but also provide a context for our understanding of world religions. They portray a world in which humanity began in relationship with God and has an understanding of him. In Romans 1:19–23, Paul writes that humans continue to have a sense of God, and creation itself witnesses to his existence.

The Bible leads us to expect that humans would seek God and, as a result of the fall, that such seeking would lead to false religious traditions alongside worship of the true God. While the Bible clearly condemns misplaced worship, it doesn’t disparage humans’ need for God or their innate, if sometimes suppressed, knowledge of him.

This inner longing of all people for God was well expressed by the great Christian leader St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD) in his Confessions. He wrestled with people’s attempt to worship God without knowing him, or at least without having revealed knowledge of him. He concluded that the rise of non-Christian religions was due to the naturalness of the human search for God and the fact that to know the true God one needs instruction. This is the evangelistic task before us. The big question is how do we go about it?

Christians are familiar with the story of the Good Samaritan found in Luke 10:25–37, and preachers often cite it as an example of how we should treat others. Samaritans were the equivalent of modern-day Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons, or Muslims. They shared some aspects of Jewish beliefs and practice. They even claimed that they worshiped the same God. But Jews saw them as heretical cultists and wanted nothing to do with them because they watered down Jewish laws and practices.

This story can speak to our situation of relating to non-Christians. In the parable, Jesus recognized and praised the Samaritan’s good deeds, but he did not take the next step of saying what the Samaritan believed was true about God or an alternate path to God. What Jesus shows us is that it is possible to recognize the good in someone of another faith without agreeing with all of their beliefs.

A similar situation occurred when Jesus encountered a Roman centurion in Matthew 8:5–13. When the centurion asks Jesus to heal his servant, Jesus praises him: “Truly I tell you, I have not found anyone in Israel with such great faith.” Some interpret this passage to indicate that the centurion was not a Jew but was on the way to converting to Judaism. Yet the passage gives no such indication. As a Roman centurion the man, as part of his duties, would have regularly offered sacrifices to Roman gods and vowed allegiance to Caesar, who was recognized as a god. What does this tell us?

The consistent message we get from Jesus is that we must meet people where they are. This does not include approving their beliefs or arguing, like Bishop Spong and Gretta Vosper, that we must abandon Christian orthodoxy to embrace a “new situation.” Jesus said nothing like that. Instead he recognized that people are complex and, unlike him, we do not see their hearts or know their inner thoughts.

Whether people are Buddhists, Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims, or followers of another religious belief system or none, they are all made in the image of God and have a personal history we rarely know. Our duty is to befriend them, help them understand the gospel, and invite them to accept Jesus as their Savior. God alone sees their hearts; we must be careful how we respond and not condemn.

To respect them as God’s image-bearers, we need to make an effort to understand them, what they believe and why, and the way they live. That is part of seeking to see them with the eyes of Christ and to reach out to them wherever they are.

Unfortunately, today we live in an age of instant results, and this can cause us as Christians to see conversion in a similar manner. Sudden conversions are biblical and possible, as we see in the experience of the apostle Paul, St. Augustine, John Wesley, Billy Graham, and many other Christians through the ages. Many people experience slow conversions that take place over many years. This was something I learned from Francis Schaeffer at the Swiss L’Abri. At first, I was shocked by the lax attitude L’Abri had in encouraging people to make a confession of faith. When I asked Schaeffer about this, he said something to the effect of, “Wait and see. If you stay in touch with us for long enough, you will learn that God is in charge and many people become Christians after long years of slowly struggling to understand.” Experience has taught me the wisdom of his words.

The above article is excerpted from Encountering World Religions: A Christian Introduction (Zondervan, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Irving Hexham. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com. Pages 20-24. All rights reserved.

Encountering World Religions and Understanding World Religions are published by HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Inc., the parent company of Bible Gateway.

BIO: Irving Hexham (@irvinghexham) is professor of Religious Studies at the University of Calgary and adjunct professor of World Christianity at Liverpool Hope University. He has published 27 academic books, including Encountering World Religions, Understanding World Religions: An Interdisciplinary Approach, The Concise Dictionary of Religion, Understanding Cults and New Age Religions, and Religion and Economic Thought, plus 80 major academic articles and chapters in books, numerous popular articles, and book reviews. Recently he completed a report for the United Nations’ refugee agency on religious conflict in Africa and another for the Canadian Government’s Department of Canadian Heritage on Religious Publications in Canada. He is listed in Who’s Who in Canada and various scholarly directories. In 2008, he was honored at the historic Humboldt University in Berlin with a Festschrift, Border Crossings: Explorations of an Interdisciplinary Historian (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag).

Study the Bible with confidence and convenience by becoming a member of Bible Gateway Plus. Get biblically wise and spiritually fit. Try it right now!

The post How to Live Your Faith in a Rapidly Changing Multi-Religious Society appeared first on Bible Gateway Blog.